The first summer Souled Out came to Israel, they arrived with a bus full of American teens and youth leaders. They were a youth group from Chicago headed by Ed and Cathi Basler, and they had come to spend an entire summer month in Israel—to find a way to bless Israel. The goal was to meet Israeli believers and get a pulse of what God was doing among the youth in Israel at the time. They met a few local believers—among them were my parents—Ari and Shira.

The following summer they brought another bus full of American teens and youth leaders with enough room to include a few Israeli believers in their program. Three of us Israeli believers joined—my brother and I, and another kid named Stefan (who today works with us at Maoz’ Fellowship of Artists). The plan was to hit the streets with worship and dancing to reach everyday Israelis with the message of Yeshua. For Souled Out, however, no outreach would be attempted before the entire team spent time learning about Israeli culture with a local Israeli evangelist.

The following summer a few more Israeli believers joined and less American teens could fit in the bus. Every year following, the trend continued—more Israelis, less Americans, until finally, a little over a decade later, the reins of leadership were handed over to locals to continue the work entirely by and for Israelis. I won’t say everything about this process went smoothly; nothing in Israel ever does. However, I will say that I can’t think of another “outside” ministry that has had both the “at the time” and “long term” impact that Souled Out had on my country because of their approach to reaching Israelis.

I don’t know if it was intentional from the beginning, or if they just followed the stepping stones the Lord gave them along the way. But the pattern of humbly bringing what they had to offer to the people of Israel long enough to show local leaders how to do it (and then letting them adapt it into a more Israeli expression) is the difference between outside ministries that sprinkle rain on the Body in Israel, and those that dig wells for us to drink long term.

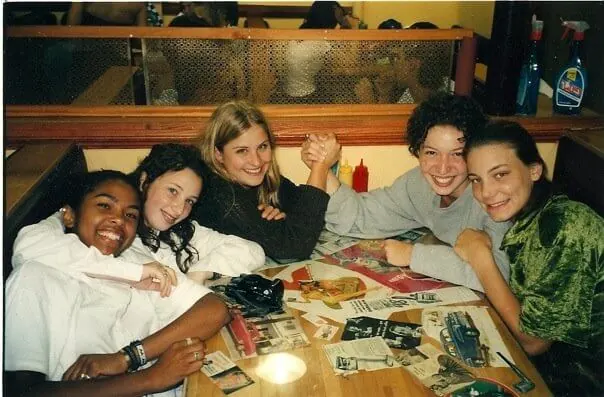

Shani (right) out with friends from Souled Out in Chicago

The Year before Souled Out

It was December 1995 and I was moving back to Israel. I had completed just over a year of high school in a tiny town in east Texas—“population two shrubs and a tree” as they liked to say there. My parents felt a year away from the spiritual intensity that is Israel would do me good, so they sent me to a ranch for teens out in the middle of nowhere. They had one stoplight in the whole town and the annual parade extended what seemed like a few hundred feet from the school through that stoplight.

The boys in my high school wore tighter jeans than the girls, and liked to stuff a can of tobacco dip in their back pocket. Having that round circle from the dip can faded onto their back pocket was the essence of cool. Though the town was tiny, the public high school, with over 1,000 kids, was the biggest I had ever attended. Their country accent was incredibly thick and I remember at least once getting questions wrong on a quiz because I literally couldn’t understand what my math teacher was saying.

I had heard of cheerleaders before I came there, but this school also had “Belles.” I never quite understood the difference, but the Belles had more glitter on their outfits; they wore sparkly cowboy hats, always bobbed their heads to begin a routine and had these “spinny” sticks they threw around like you see in gymnastics at the Olympics.

There were white and black kids in the school and everyone mostly got along—until they didn’t. Growing up in Israel, I only understood the world to be divided into cultures and citizens of different countries. Israelis—having immigrated from all over the world—had a wide variety of skin tones, as did my parents. So, skin variety within a country meant nothing to me because I had yet to learn American history. Once in the cafeteria line I mentioned in passing my father being dark-skinned and that he had sported an “Afro” in his younger years. All the black kids in the line got so excited that my daddy was “one of them.” It was really cute—any teen wants to feel accepted into a special category—but I had no idea why it mattered so much to them. As far as I was concerned, the only categories I clearly fit into were Israeli and Jewish—and in those categories I was entirely alone.

To this day I am probably the only Jewish person many of my former schoolmates will ever meet. And while many of the students and staff were excited about the idea of going to school with an Israelite, very few of them understood that meant going to school with someone of a different culture who processed the world differently. My feisty “Israeliness” got me in trouble more often than it didn’t, and I often spent hours in detention with no clue what cultural taboo I had violated. Still, with all the awkwardness, my time in east Texas played a defining role in my life and relationship with the Lord and I wouldn’t trade that time for the world.

In the spring of 1996, I visited Israel on spring break and attended the now infamous national Youth Conference. That summer I returned to Israel for summer break and spent a month running around Israel with some of the coolest people Chicago ever produced, as far as I was concerned.

It was now December and I was going home for good—back into the spiritually challenging land of Israel. Ed and Cathi Basler invited me to spend winter break with their family and all the friends I had made during the summer months in Israel. It was the first time I got to experience American family holiday traditions—and the first time they’d had an Israeli join them. Despite me explaining in my classy Israeli teenager style that “Christmas was stupid,” they had presents ready to give me as everyone sat in their jammies Christmas morning. From the birthday cake they baked for Yeshua to the bizarre cats-with-different-sized-bells-display-thing that rang out Christmas melodies, the experience was a cultural smorgasbord.

Apparently, I went home and talked up the fascinating experience, because every year going forward, the Basler’s home became the coveted place for Israeli believers to be invited for winter break. For the record, being Jewish, I hadn’t grown up with Christmas and the experience didn’t make me want to celebrate Christmas going forward, but I very much enjoyed the family warmth they had to offer and how they made a point to celebrate Yeshua and His Jewish origin.

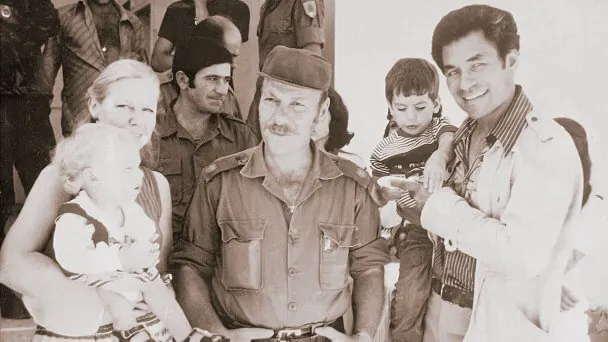

Souled Out meeting at the Heart and Soul cafe in Chicago

Souled Out Impacts Israel

I returned home to finish out my 11th grade year and when the summer arrived, so did the Baslers with a busload of Souled Out teenagers. There were several things that made their visits so influential to our then-small and geographically spread-out group of Israeli believers. First, young Israeli believers were used to being the only believer in their school or town. And they were accustomed to small congregations with simple worship on a guitar or piano. And while some of the “larger congregations” that had 50-100 members enjoyed classes during the services for young kids, there weren’t really programs for teenagers. Suddenly, dozens of literally sold-out-to-the-Lord teens showed up at our doorstep offering friendship and even helping us find other believing friends locally. It had the “fresh troops” effect on us in Israel.

Second, as this was before the age of media access on the internet, Souled Out brought lots of tapes and CD’s of Christian music that Israeli believers didn’t even know existed. This proved an effective alternative for believing youth who were struggling with the pull of unedifying worldly music. Third, Souled Out understood that building long-term relationships was the key to making a lasting impact in Israel. So, when they came, we did outreaches together on the streets, but it was clear their priority was spending time with us, befriending us, and encouraging us.

One of the Basler teens recently reminisced, “I remember one of our first visits hanging out with some Israeli teens when a pastor’s kid asked me, ‘Are you guys going to leave and disappear just like all the other groups who come here do?’ She was so emotionally tired of making friends with amazing internationals who just came for a short time and then disappeared without a trace. I told her, ‘We want to be here for you for a long time, and as long as God keeps opening the door for us to come into the country, we’ll be here. And when we’re in the U.S. we can write and call each other.’ They kept that promise and came even during times of upheaval when buses were being bombed and rockets were flying overhead. If anything, they recognized Israeli believers needed them more during such times. They came during summer break, winter break —and then sent smaller groups every few months in between.”

In hindsight, Souled Out’s destiny seemed to be directly intertwined with their work in Israel. They became a bonafide youth group the year they began coming to Israel. And without planning it, the year they handed the reins over to local Israelis, their work in Chicago also ended. And though a time came where the trips to and from Chicago ceased, I can say with certainty many Israeli believers my age (myself included) are who we are today in large part because of the friendships and experiences we had with Souled Out.

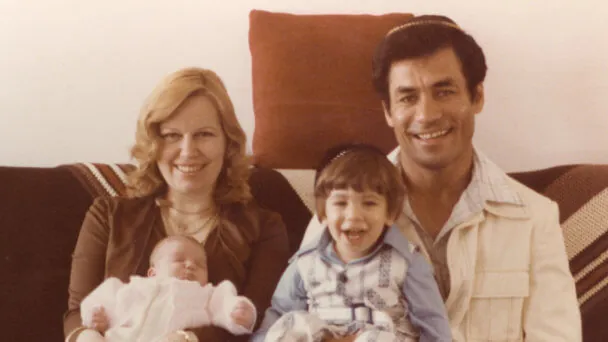

Ed and Cathi Basler with their four children and Ayal Sorko-Ram (right) who spent a year with them while in high school

How Souled Out Began

The Baslers birthed Souled Out in their living room almost by accident. Ed and Cathi had four kids (one adopted as a teen), and when their kids would bring over friends, Ed and Cathi (or Mr. Ed and Mrs. B as everyone called them) would hang out and love on them. The Basler home, just outside of Chicago, became known as the place to be if you wanted to hang out but not necessarily go out. It also became known as a place where kids who didn’t get a lot of love at home could go and enjoy a warm family environment.

Even before she was married, Cathi had a heart for Israel and even considered moving there. Although it didn’t pan out for her to live in Israel, that never dampened her passion for the people of Israel. Taking care of the youth who flocked to her home came naturally, but taking on young Israeli believers became a must in her book when she heard the desperation of believing Israeli parents. “The Lord called us to Israel,” these pioneer Israeli believers lamented; “We left everything and brought our families here. We have worked tirelessly to build a community of believers and raise up our kids in the fear of the Lord the best we know how. Then, at 18 years old, we are required to sacrifice our children; hand them over for several years to serve in the army—an incredibly secular and all-consuming environment—and we get our kids back broken and godless.”

The days following PM Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination, Ed and Cathi were in Israel again. If there was a time to experience the depth of Israeli youth this was it. In the aftermath, the Baslers and my parents walked through the downtown Tel Aviv plaza where Rabin was murdered, and where for weeks young kids gathered weeping, singing songs, or lighting memorial candles and staring aimlessly into the flames. Something had to be done to address the condition of Israel’s youth— Israel’s future—and they would start by strengthening a small number of Israeli-believing youth first. The timing couldn’t have been better as my parents had been wrestling with what to do with my brother and me (who were struggling through our teen years) and had already planned a national youth conference for the following spring. When Ed and Cathi heard about the conference they asked if they could send their youth leaders to participate and further learn how Israelis did ministry. The rest is history.

All Grown Up

Eitan Shishkoff, who immigrated to Israel in the mid 90’s and planted a congregation in northern Israel. Having a deep passion to reach Israeli youth, he got involved with Souled Out in the early 2000’s. By around 2005, the Basler’s sensed their “baby” was growing up and it was time to begin a hand off. They spent the next couple of years training, strategizing, and passing on everything they knew to those who would take the reins and run with the beautiful work they had begun. The work would become a joint effort of Israeli youth leaders from all over the country with Eitan at the helm. Eitan would eventually rename the work that continues in Israel to this day, Katzir—the Hebrew word for “harvest.”

How it all began

When Ari Met Shira

The First Congregation

The War, the Immigrants and the Training Center

Israel’s Second Underground Railroad

The Major and the Millionaire

Diary of an Israeli Soldier

The Right to Exist

Never Say Never

The Birth of Tiferet Yeshua

A Spark in the Dark

The News & The Police

Souled Out Comes to Israel

Israel Wrestles with Democracy