Joseph (not his real name) was nine when his grandmother boarded a plane to the Holy Land and left him alone at the airport in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Someone had messed up. He was supposed to be on that flight, but his promised ticket had not arrived. Paperwork in Ethiopia is a messy thing. Joseph doesn’t have a birth certificate, so he isn’t actually sure he was nine at the time, but it was close enough. Still, as chaotic as the system was, they couldn’t allow him on the plane without a ticket.

His grandmother couldn’t stay with him. She had been on a waiting list for years and if she missed this flight, she might never get another chance to leave. The Jewish agency promised he would be on the next flight out the following day, but until then he was on his own. Joseph grew up in an isolated village and only moved to the city with his family for a few months as they awaited their turn to fly out. So when he left the airport alone that day, he had to guess his way back to where his mother was staying with his brothers on the other side of the city.

Because of the hostility Ethiopians had towards their Jewish population, Ethiopian Jews often lived in villages rather than in big cities. Though they had lived in Ethiopia for thousands of years, they were nicknamed by locals Falasha—invaders.

When anything went wrong in Ethiopia—anything from the curse of a witchdoctor to a strange illness or natural disaster, it was always the fault of the Jews. The more isolated their community, the less they experienced the persecution. There had been periods when they were not allowed to own land as Jews, but in the villages they were at least freer to maintain their Jewish identity and traditions.

Strangely, while Ethiopians reviled local Jews, the government nonetheless had no interest in letting them leave the country. Ethiopia, being a communist country, meant many backroom deals had to take place to rescue Jewish Ethiopians. Some of the deals could only be made with neighboring countries which required Ethiopians to trek on foot across their country into Sudan before they could be airlifted to safety. In the 1980’s and 90’s, Israel sent many planes to airlift tens of thousands of Jews from Africa.

Jerusalem the Mythical

To Jews in Ethiopia, Jerusalem is a mythical land of paradise. In Ethiopia they even have a song they sing to the migrating storks. In it they ask—“Oh stork, how is Jerusalem our land?”

So when Joseph finally arrived in Israel to be reunited with his grandmother and cousin, he was sure he had arrived in heaven itself. Upon landing, however, he was handed a gas mask. At the time, Joseph remembered feeling so grateful for the gift—any gift really. That was until the sirens went off and everyone’s panic made him realize the mask was to help keep him alive. It was during the Gulf War, and Israel was being fired upon by Iraq’s Saddam Hussein.

When the war ended a month or so later, Joseph began the slow and tedious process of assimilation into Israeli culture. His mother and brothers joined him within a few months of his arrival, though his step-father (his father had died before he was born and his mother had remarried) wouldn’t be able to join for another two years. Needless to say, the road ahead would be long.

Credit: Alamy/travelib Ethiopia

The Plight of Ethiopians

Israel is good at responding to emergencies. So, when the Israeli government realized the plight of Ethiopian Jews, planes were chartered, and complex and even dangerous military operations were executed to rescue them and bring them home. What Israel wasn’t great at, was considering the vast cultural gaps between Ethiopian village life and modern Israeli life, and then planning out long-term cultural assimilation solutions. This would explain why the assimilation process for Ethiopians was a bit like hitting a brick wall and then sinking into quicksand.

Having come from nations all over the world, Israelis are used to different skin tones in the Jewish community. But it was the association of Ethiopian Jews with their ancient culture that made it difficult for immigrating Ethiopians to get past stereotypes. Overcoming stereotypes from the outside would be one thing. But, perhaps the most difficult challenge they would encounter was that of their family structure.

In Ethiopia, the husband was the exalted head of a family unit. He was part of a hierarchy that was respected and revered. The man knew his place, and enjoyed the satisfaction that comes with providing for his family. The women occasionally worked in nearby fields, but their primary job was homemaker.

In Israel, the men and women were equal legally and culturally and women worked jobs just like the men. When it came to learning the language and adjusting to the new culture, the women often fared better than the men. Work opportunities were the same for both men and women, and the wives who had previously been dependent on their husbands’ skills in agriculture or a local trade, could now bring home greater incomes. The father, no longer the knight in shining armor, now struggled to discipline his kids, who had learned the not-so-subtle art of Israeli chutzpa.

This new paradigm began to tear at the family fabric. Youth found their new role models in the black American rap culture. The young generation of Ethiopians so intensely desired to be part of their new land that they embraced Hebrew and refused to speak Amharic. This furthered the disconnect between the generations who were previously very tight knit.

Despite Israel being a land of immigrants, Israeli culture tends to be tribal and does not always quickly embrace newcomers. So, while the young generation had abandoned their Ethiopian roots, they still had ways to go before they would master Israeli culture. This state of limbo between cultures resulted in an identity crisis for many Ethiopians. The fathers had lost hope they could build and support a family, and the younger generation was losing hope they would ever feel like they belonged. This vulnerability made some susceptible to street life and substance abuse—and everything that comes with that scene.

Credit: Shutterstock/Magen

When Yeshua Came Himself

Joseph’s family moved several times during his childhood, experiencing difficulties at each stop, and eventually settled near Haifa. In one of those locations, his grandmother came home one day to see her apartment being broken into. The trauma of the experience gave her multiple heart attacks and within months she passed away. It was just one more hit to the once-loved fantasy of a beautiful Israel.

Still, it wasn’t all bad. With immigrant subsidies from the government, they were eventually able to purchase a small apartment. Joseph was a teenager by this time and attended a religious school. He was zealous about everything he learned and often served as the cantor during ceremonies.

He was close with his family, but when his mother came home one day and explained to him and his father that she believed in Yeshua, Joseph was livid and threatened to report her to the authorities. He and his step-father formed a bond in their opposition to what his mother had done. It would take some explaining, arguing and praying, but eventually Joseph’s father came around as well.

When Joseph heard this, he was beside himself. In one of their arguments his mother tried to explain how real Yeshua was to her, but Joseph finally responded, “If Yeshua is real and wants me to follow Him, He can come tell me Himself.” A few nights later, Yeshua came and spoke to Joseph Himself.

Being a devout Jew, Joseph had never heard much about Yeshua—except in bad generalities, of course. So seeing Him in a dream sitting on a throne surrounded by bright light did not happen because of any previously seen or described imagery. “It was so real, even years later,” he said. “It’s as real as you sitting in front of me. He spoke to me for a while, and as He spoke it was like His words went inside me, changed me and filled me with the power to do what He was asking me to do.”

Joseph woke up and immediately told his mother, “I believe.”

“My friends, classmates and teachers were vicious towards me,” Joseph said, thinking back on the early days of his born-again life. “Our Ethiopian friends screamed at us, ‘We left Ethiopia to get away from people who believed like you!’”

“I knew what I believed was real, but it was difficult for me to take another round of social rejection. I had spent years learning the language and culture and had finally made friends—and now I was figuratively leaving everything again. Still, I could feel God close—like a mother who holds her newborn.”

“Some of my classmates tried to get me in trouble with the principal, but while he was hearing rumors about my new beliefs, he was also hearing about me volunteering my time to help others in need. So, while everyone standing there was expecting him to berate me, instead he was suddenly encouraging the other students to act more like me.”

Credit: Shutterstock/Glinsky

From Barely Surviving to Thriving

Joseph had always enjoyed helping others and doing it with his whole heart, so with his newfound knowledge of Yeshua, he quickly found his place in the local youth group and worship team. After high school he went on to study economics and business management. He received a scholarship that covered his education and housing but when it came to food and other basic items, he was on his own. So he worked at everything from cleaning to tutoring. “Sometimes, there was no regular work, so to get money for food, some of us worked as political activists in those days. We didn’t care what the party was or what the signs said. It was about survival. We just knew we’d be paid the next day and would be able to eat.”

University was challenging, but during that time Joseph got to know the woman he calls to this day “my lady.” He talked her into coming to study at the university with him where they would both get their degrees. And eventually with the blessing of both sides of the family, they planned their wedding. Though they were among the first do to it, their decision to blend Ethiopian traditions into an Israeli ceremony felt natural as they understood the importance of embracing their new world without rejecting the old one.

After they married, Joseph was drafted into the army and there, as seemingly everywhere else, he excelled. Upon completing his service, he considered how best he could be a blessing both to his community, and to God’s kingdom. He was good at business and economics, and had a heart to help people especially in complicated legal or business matters. He did his internship in the Knesset and within a few years had established his own practice as a lawyer. It was never about going at it alone, so he connected with dozens of other Ethiopian lawyers for collaboration. He also volunteered his time working with youth and tutoring new immigrants in Hebrew, and even offered his legal services for free to the less fortunate.

Things were going good. No. Things were going great!

If his goal in life was to help people and make a good living doing it, he was on the right path.

Credit: National Library of Israel

When Silence Speaks

Joseph’s reputation was growing when a few large companies approached him. One of the job offers included work he loved and flying back and forth to Ethiopia. There was no reason he could see not to take the job so he began the training process.

However, when Joseph arrived in Ethiopia on his first trip, he ran straight into a wall of silence. No internet, no phones, no TV. No distractions. “It was overwhelming at first,” Joseph shared. “I’m a guy who’s constantly surrounded with people and activity. And suddenly my ears were ringing from the silence. Suddenly, it was just me and my Bible and God. And all I could hear was Him telling me I was supposed to be in ministry.”

His career wasn’t an easy thing to give up. It was worthy work and he loved it. In this current line of work he knew his family would be taken care of financially. Life as a minister could mean he would struggle to provide for the woman and children he held dear. Grasping the gravity of the decision he needed to make, he decided to go on a 40-day fast. After all, this was what people in the Bible did when they were at a crossroads in their life.

By the end of the fast the answer was clear. What wasn’t clear was how the love of his life would feel about his decision. She knew the ramifications of such a decision.

Her response floored him. “When you asked me to marry you, you told me you were going to be a minister. I’ve been waiting for you to keep your promise.”

“Looking back, I know if I had continued in the path I was on, I would already own my own home and my family would be surrounded by the goods this world has to offer. But I also know we would be miserable in the midst of it all because the one thing the world cannot offer, for any amount of money, is the joy and peace that comes with the knowledge you are in God’s will and He is pleased with you.”

Shutterstock/Paluchowska

Next Generation Ethiopians

It’s a natural occurrence for immigrants from Russia, Ethiopia, America, Asia and Latin America, to name a few—who are believers—to plant congregations in their native tongue. Those congregations attract other immigrants like them and are an incredible source of fellowship and spiritual encouragement in a challenging country such as Israel. What comes less naturally and must be a conscious effort is the transitioning of any such congregation to the Hebrew language once enough of the congregants have been in the land for years.

The only other way a Hebrew-speaking congregation will be birthed is when the Sabra generation (native-born) or those who came at a very young age and grew up in Israel, branch out to plant an entirely new work. And this is exactly what Joseph had in mind when he laid out the vision for their congregation. It would be the first Hebrew-speaking Ethiopian congregation in the land.

“I knew my people had a deep desire to be a part of Israeli culture so I understood it was crucial that our spiritual expression would be just as Israeli if we were going to raise up the young generation of Ethiopians in Yeshua.”

Joseph and his wife gathered their three small children in the living room and began to pray. Soon, friends began to join and very quickly their entire apartment was packed for each meeting. With the meetings taking place in a residential area on Shabbat, the neighbors soon began complaining about the noise from the worship and fellowship.

Today, the less than two-year-old congregation has moved to an industrial area and continues to grow even during the pandemic. Especially in this small country, the rate at which this congregation has grown is evidence of how ripe the harvest is among Hebrew-speaking, Ethiopian Israelis. So it comes as no surprise that God chose someone with such a deep, spiritual passion and commitment to serve his generation. God knows there’s a lot of work to be done.

Happy Passover!

What is a Promised Land?

The Scariest Parable in the Bible

Restoration of Our Land

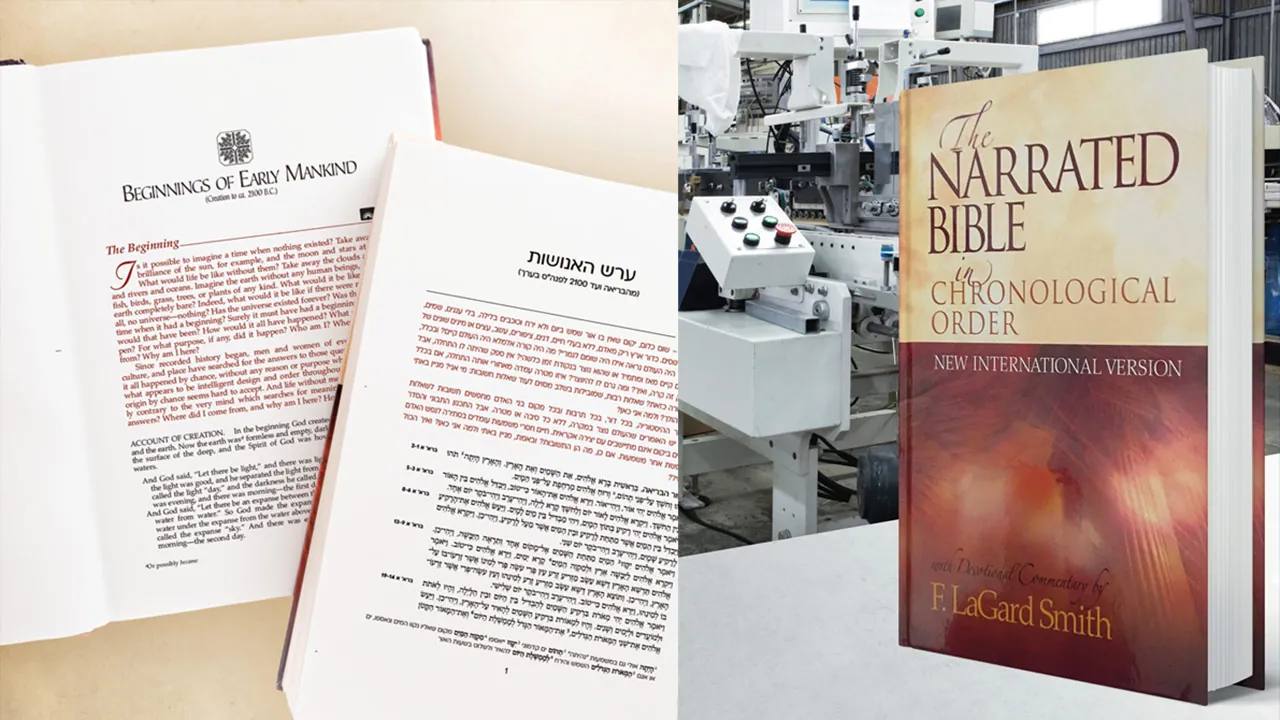

What Makes this Hebrew Bible Different From All Others?

Two Miracles and a Message

Narrating Hope

Hope in Action

Fight to the Finish