When we left for The States to seek help for our son’s serious learning issues, our congregation of over a hundred Israelis in a suburb of Tel Aviv was strong and vibrant. From the meeting hall to children’s Shabbat classrooms to admin offices, something was happening in every square inch of the Maoz Center we had built.

Two years later, upon our return, the facility stood empty. The empty ark (cabinet) where the Torah scroll had been kept—and a hundred chairs stacked in the corner of the basement where the congregation had met—were the only evidence that anything had ever happened there. There was little left to do but to move our family to the upper floor for the time being, until we decided on our next step.

We had returned during the summer of 1990 in order to have time to get settled before our son Ayal and daughter Shani would begin their next school year. But before September rolled around, three significant events began to unfold that would make the following year one of the most spiritually exhilarating and emotionally tasking years we would experience in Israel.

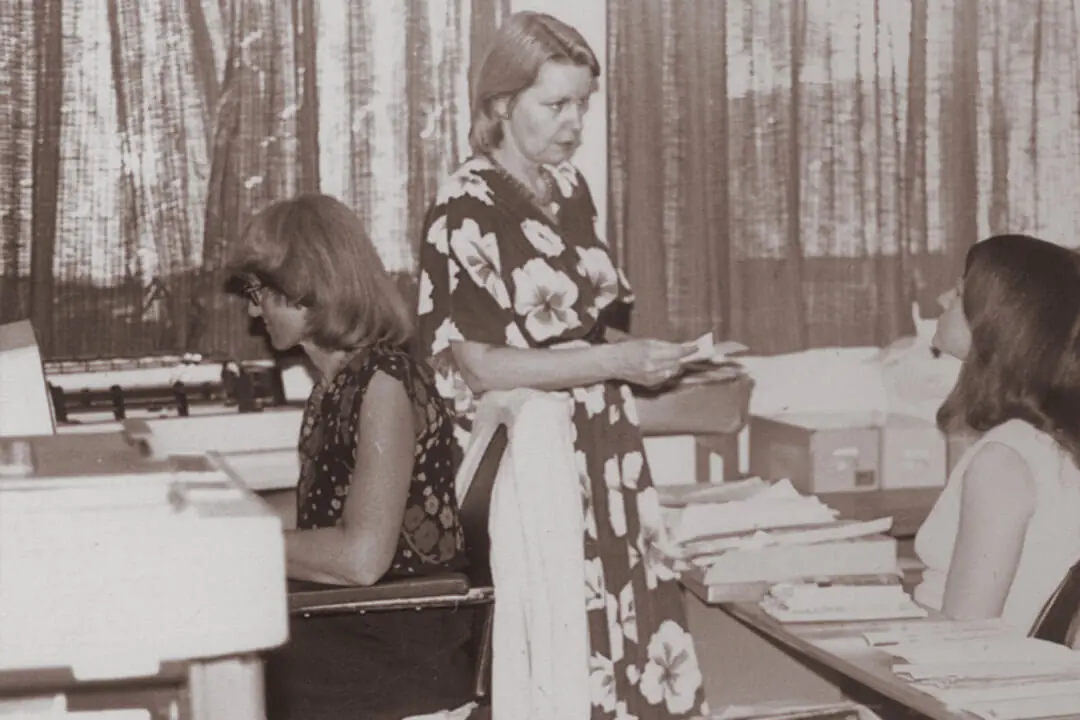

At the height of activity at the Maoz Center in the 1980’s, Ari and Shira’s guest room became the office and the Sorko-Rams moved into a mall apartment across town.

The Gulf War

Within a month of our return to Israel, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. Thirty-five nations, led by the United States, stood up to Saddam and by mid-January Kuwait was free again. However, when victory was declared, no one in Israel breathed a sigh of relief. Saddam had made plenty of threats of his intentions to gas Israel off the map with his “mother-of-all wars” and all that. Israel distributed gas masks to its inhabitants and families held their own private drills with their kids to make sure everyone knew what to do in case of attack. We made it fun for our kids and drilled them with a timer. By the time we were actually attacked, they could go from play to fully suited up in about two minutes.

At 2:15 a.m. January 18th the first scud missiles were fired on Tel Aviv. We awoke to shrieking sirens. As prearranged, Ari went straight to the front door to let in an elderly couple who lived down the street and I went to wake Ayal. Ayal, who was a tornado of activity in his waking hours, slept like a rock.

“Ayal! Wake up!” My pleading and shaking did nothing to stir him until the first explosion hit. Instantly, Ayal bolted from his bed and ran to Shani’s room—as it was our designated “safe room”—and threw on his protective gas mask and suit. We had long since sealed the one window in the room, so Ari simply closed the door and taped plastic around its edges. Then the six of us—plus the family dog—sat in the bedroom waiting for the promised instructions that would come on radio and TV if we were attacked.

Shani fell asleep during one of the attacks. Her dog also managed to rest with his makeshift “gasmask” of a wet cloth and baking soda which the government recommended.

It was at least 30 heart-pounding minutes before the TV and radio stations pulled their act together and switched from regular programming. Finally, the reassuring voice of Nachman Shai, a largely unknown army spokesperson, came on the air to explain that Israel had just been fired upon but that everything was under control. In between his instructions that night, the station played hours of Israel’s folk songs about love of land and country. Four hours later, about the time I started wondering how we would know if the oxygen levels in the room got too low, Nachman Shai released the nation from their rooms. Schools, of course, were canceled until further notice.

According to the papers, during this very first missile attack, 668 buildings and 1,000 apartments were damaged or destroyed in the Tel Aviv area alone. Thousands more were hit in the coming days and nights. But no specifics were given by Israel’s state television, so Saddam would not receive “feedback” on where to fire his next missiles.

Even though the Scud missiles almost always came at night, Israelis carried their gas masks everywhere they went. The unpredictability of the sirens and the fact that in some areas the sirens could hardly be heard had everyone jumping anytime a motorcycle revved up its motor or the refrigerator made a strange sound. To help resolve the issue, Israel set up a dedicated silent radio station that would only broadcast sirens and emergency updates during attacks. Still, despite the emotional toll, Israelis were quick to adjust to the new norm and kids busied themselves with decorating their gas mask boxes.

Gas masks were distributed in a box with a strap so Israelis could keep it with them at all times.

Ayal and Shani began going to bed in their regular clothes, as pajamas were too awkward to stuff into the gas suits. And just like kids all over the country, they learned to fall asleep with their gas masks. The dash for the safe room, donning of gas masks and missile explosions followed by Nachman Shai, the army spokesperson calming the nation, became a routine part of Israel’s nightlife. In an amazing display of trust, Israelis followed Shai’s instructions to a T.

While a total of thirteen were said to have died of heart attacks and the like during the assaults, only one is believed to have been killed directly from missile fire–a miracle, considering the massive damage Israel sustained during that time. Towards the end of the war, one missile flew right over the top of the Maoz Center and fell into the Mediterranean Sea two miles away. Though the attacks on Israel lasted only six weeks, they left their mark on the culture. At the time, no one knew if and when it could start up again. No matter what we said, Ayal and Shani never went back to wearing their pajamas to bed.

The most unique part of this time period, however, was the openness of Israelis to hear about God. Our confidence in the Lord at a time when Israelis were shaking in their boots gave us unprecedented opportunities to share about Yeshua everywhere we went. Suddenly, what people believed about God and life after death was front and center in their minds. The significance of this moment in time was clear to believers across the nation who were experiencing the same openness from those around them.

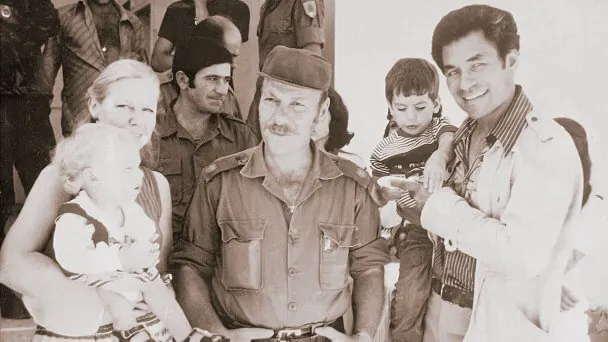

In the “safe room” with friends who were visiting when the sirens went off

Sudden and Massive Wave of Immigration

In 1990, the population of Israel–just a generation old–was almost four million! Much of the infrastructure was just developing and life had a small-town feel; everyone had a sense that building up the nation was part of their individual and collective destiny.

In the years leading up to its fall, the Soviet treatment of Russian Jews began to garner international attention as thousands of Jews were forbidden to leave their country and were often imprisoned. Their crimes included studying Hebrew, practicing Jewish traditions, or applying for a visa to immigrate to Israel. Such behaviors were an assault to communist ideology that had no use for any form of religious belief. Interestingly enough, the Soviets highly valued the great intellect, skills and achievements of the Jewish population and, as such, had a vested interest in prohibiting them from abandoning the motherland.

But with the collapse of the U.S.S.R. and the Iron Curtain, hundreds of thousands of Russian Jews who had dreamt of coming to the Land of Promise were released to do so. It was like the bursting of a dam.

The trickle began in 1988, and a stream continued in 1989. But 1990 marked the beginning of the flood of what would become 900,000 Jews and their families– added to a nation of less than four million inhabitants.

With their local currency worthless outside of the former Soviet Union, Russian Jews could not bring any wealth with them. Looking to salvage some funds, they purchased popular items before arriving in Israel and could be found trading them in bedouin markets.

Absorption

Russian Jewish culture had its idiosyncrasies. Despite their Jewish roots, they were known to like bacon, vodka and “Novy God”–a variation of Christmas that somehow took place on New Year’s Day. Up until that point, Israelis had shown little interest in any drink other than their traditional cup of wine as they ushered in the Sabbath; kosher meat was basically all you could get in the country and Christmas trees were only for monks and priests living in monasteries. When suddenly one out of every five citizens in Israel was Russian, the culture felt a shift almost overnight.

Politicians took to the airwaves encouraging Israelis to invest in Israel’s future. “We are bringing highly skilled engineers, artists, doctors and scientists into our fold; within a few years, this will be an incredible boost to our economy and culture,” they declared.

But highly-educated doctors, engineers and skilled musicians would be found cleaning floors, working at checkout counters and collecting garbage. In those days the streets were full of very skilled homeless people. For Israelis, a new phenomenon was listening to top-quality musicians playing on the streets of our cities—hoping for a coin. It was the language barrier that would be this generation’s greatest challenge to become useful in their area of expertise.

Israel had little in the ways of a luxurious lifestyle at the time. A significant number of Israelis lived in small towns or on collective communities called kibbutzim (picture a form of “voluntary communism” that was effective in helping Israelis establish communities in the early days). “You willingly give all you can and you receive what you need” works when everyone is in survival mode. But despite the humble existence, everyone still managed to find a decent place to call home.

The locals in Israel did not remain apathetic. Much brainstorming went into planning a new school year for 20,000 new students. Thousands of Israelis registered to rent out rooms to new immigrant families. Every option they could think of was being considered—including putting tents and caravans on the roofs of residential and commercial buildings so they would have access to utilities. It was a genuine collective effort and even government leaders with land ordered caravans to be put on their property to help house families.

Still, it wasn’t enough. It wasn’t just housing; it was the jobs. It was one thing to logistically fit 20 people into a three-bedroom apartment. It was quite another to feed them. It made one wonder how bad life must have been in the U.S.S.R. that this became an acceptable alternative. Though the start was bumpy, what Israeli leaders said was true. Within a few years these highly-skilled immigrants were instrumental in Israel’s medical and tech boom of the late 90’s and onward.

Perhaps the most fascinating part of the Russian immigration is that it took place while missiles were being shot at Israel from Iraq. Still, the whole experience brought real meaning to the verses in Jeremiah and Isaiah:

Surely now you will be too cramped for the inhabitants…the children of whom you (Zion) were bereaved will yet say in your ears, this place is too cramped for me; make room for me that I may live here. Isaiah 49:19, 20

A large number of immigrating Jews had come to faith through a sudden outpouring of God’s Spirit while they were still in the former Soviet Union. Men, like Rabbi Jonathan Bernis, held huge concerts of Messianic music with a simple Gospel message that saw thousands of Russian Jews come to faith. And because most Jews from Russia had never been indoctrinated to hate or fear Yeshua the Messiah, many who were exposed to the message of Yeshua came to faith once they arrived here in Israel.

Today, there are many Russian Messianic Jewish congregations in the cities across the nation. We have had the joy of walking alongside some of these pastors, and getting them enrolled into language courses so they can continue to be relevant to the Hebrew-trained children in their congregations. As the second generation takes leadership, these congregations are evolving from Russian-language congregations to holding their services in Hebrew.

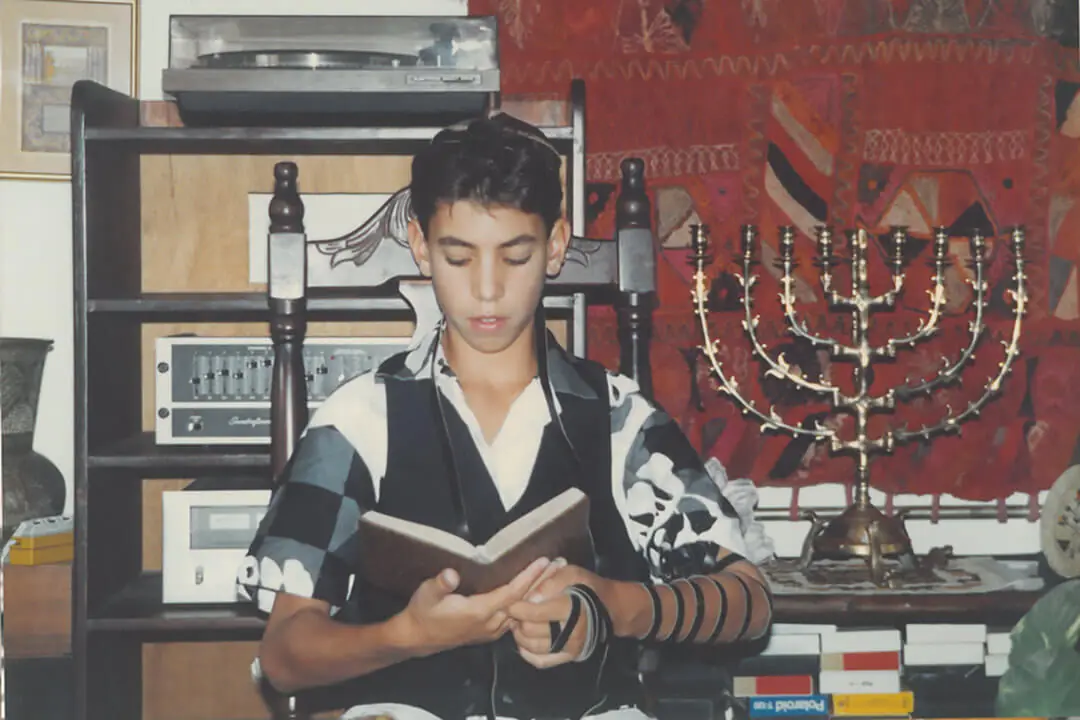

Though it was delayed a few months because of the war, Ayal and Shani celebrated their Bar and Bat Mitzvahs in the early summer of 1991. Of all the things that took place during the celebration, the part that brought the most excitement for those who knew of Ayal’s learning struggles–was watching him read his Torah portion! Read more about it in Part 3 of How it all Began (March 2021)

Training Center in Jerusalem

Arriving back in Israel to virtually start over in terms of ministry, we once again looked at the Body of believers on a national level. As pioneers, the questions we asked ourselves were not necessarily, “What can we do that we are good at?” but rather, “What does this nation need most at this stage?”

The burden to reach Israelis felt overwhelming at times. They didn’t know anything about Yeshua. They had been told so many falsehoods about Him for so many centuries. They needed to hear about Him! But we both knew if there were so few leaders to care for and disciple new believers, the long-term effects could be masses of Israelis coming to the Lord and then falling away.

I was no stranger to the vision of training up leaders. My father, Gordon Lindsay, had purchased a building on the Mt. of Olives with the dream of using it to train Israelis to reach their own people. When an Arab family stole that property, my mother, Freda, raised the funds, marched over to Israel and bought another property. The vision to train Israeli leaders was that important to her.

By late 1991, with the residue of the failed congregation still around us, several of our trusted friends, including Barry and Batya Segal, encouraged us to move to Jerusalem. “Your family is constantly moving from apartment to apartment; you need your own place. There are many believers in Jerusalem; you can start a discipleship school and when visitors come from abroad, they’ll have an easier time getting to you and seeing what God is doing in the land,” they said.

It wasn’t an easy decision but it was an open door. Having just arrived back in Israel, our teen children had to adjust back to their native tongue and the largely godless culture (after being surrounded by believers for two years). We had only been back in the country for just over a year, and now we had decided to move again. Ayal took it hard, but Shani, who had just been accepted into a specialized national sports program, cried for a good six months as details unfolded.

Pioneering often sounds glamorous after the fact, but in real time, it is more of charting a path until that direction can be followed no more—and walking back a bit to chart another path. Each time you get closer to your goal, but there are plenty of dead ends along the way. Many lessons are learned in the process, so even dead ends are often worth suffering, just for the experience it offers.

The push for a training center in Jerusalem was such a path. We put together $5,000 of our personal money for a down payment on a house of our own in Mevaseret Tzion–(a town about 10 minutes outside Jerusalem). While the house was in its building stages, we joined together with other friends and dedicated the foundations of the house to the Lord.

Once we would manage to sell the Maoz Center in Ramat Hasharon, we planned to put a down payment on a small hotel in Jerusalem that we could turn into a training center. We had the energy and the passion to teach day and night. This was about building God’s Kingdom in one of the most significant periods of Israel’s ancient story. We would raise up leaders who then would be released to do what God called them to do—no strings attached.

Oh Jerusalem, Jerusalem!

However, there were Jerusalemites who had their own plans. Ultra-Orthodox Jews who kept track of the Maoz Israel Report got wind of our plans and launched a little crusade to “stop the Sorko-Rams.” According to articles written in the local papers, they used their connections to warn people in the city municipality and other people in the local government, making sure nothing with the name Sorko-Ram or Maoz made it through any purchase or permit committee. At one point, Knesset members were publicly debating our move, as recorded on TV.

When the ultra-Orthodox got wind of the location of our newly-purchased house, they visited all the neighbors and told horror stories of what the “missionary couple” would do to them if they were allowed to move into the neighborhood. Israelis who had never seen or heard of us were terrified. They threatened to blow up our new house. The contractor begged us to tear up our contract; he would gladly return all of our down payment. The opposition wasn’t fun, but it was not intimidating. It was not the first time our home had been targeted with a bomb. We would push forward.

Then, to our surprise, the sale of the Maoz Center in Ramat Hasharon fell through. A few nights later, I had a vivid dream in which the Lord showed me we were not to move. When I awoke, Ari received a phone call from the real estate agent that they had a serious buyer. Having just heard my dream, Ari informed him the house was no longer for sale.

Meanwhile, our good friends Barry and Batya Segal, who had purchased a house next to us near Jerusalem, were informed that the house they purchased had some serious structural issues. The timing was perfect; we canceled our contract and the contractor transferred that house we had dedicated to the Lord, to the Segals.

We had prayed and moved forward in faith. In the end, it was clear, the Lord wanted us to stay in the Tel Aviv area. The funds we had raised were nowhere near what Maoz needed to establish a leadership training school and so we sought the Lord for other ways to grow His Kingdom. Of course, the goal could never be a building; the building was merely a tool. The goal was mature leaders who could shepherd and train young believers in the Lord. Now it was time to back up a bit and move forward again.

How it all began

When Ari Met Shira

The First Congregation

The War, the Immigrants and the Training Center

Israel’s Second Underground Railroad

The Major and the Millionaire

Diary of an Israeli Soldier

The Right to Exist

Never Say Never

The Birth of Tiferet Yeshua

A Spark in the Dark

The News & The Police

Souled Out Comes to Israel

Israel Wrestles with Democracy